The Author

Fay Bound Alberti

Standardising healthcare: the case of face and hand transplants

In April I was invited to speak at a U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) held a public committee workshop exploring how to standardise care in face and hand transplants. Hand and face transplants are forms of vascularised composite allografts (VCA) and to date they have developed without an international consensus on best practice. This is in stark contrast to other forms of transplantation, especially solid organs.

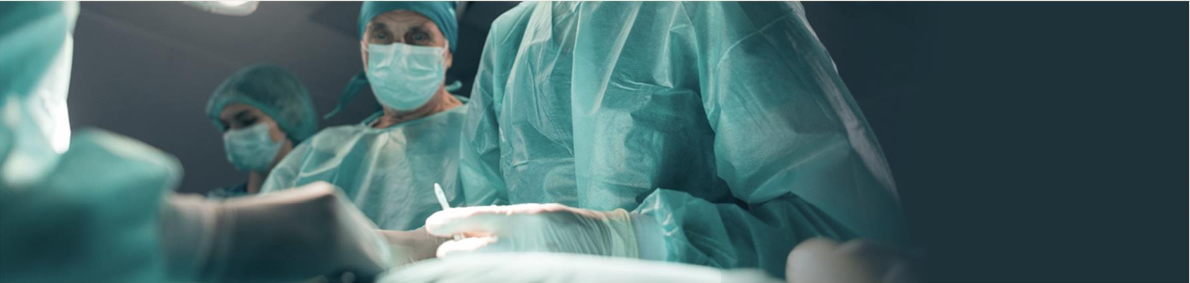

My project Interface has previously raised concerns about this disparity, especially considering how patient viewpoints have historically been neglected. In 2022 I held a Policy Lab at King’s College London with my project Interface (then AboutFace) to investigate why there wasn’t a standardised approach to face transplants, and what could be learned from bringing together experts from different sectors, countries, and perspectives. Our recommendations were made available online and developed into a publication for the American Journal of Transplantation.

This NASEM committee forms part of an important move towards recognition of the need for standardised care for hand and face transplant surgeries.

I spoke alongside surgical experts and patients, as the committee workshop brought together international perspectives from across the field of hand and face VCA, and a wide range of geographical regions. The workshop was held in two parts: patient perspectives first, followed by specialists in medicine and ethics. Face transplant recipients included Robert Chelsea and Carmen Tarleton; hand transplant recipients, Sheila Advento, William Lautzenheiser, Laura Nataf and Daniel Benner, all of whom brought important perspectives to bear on the question of patient experience. All talked of the health challenges involved in their journeys, and what they wished they had known before undertaking the surgery.

Some of those patients present – like Robert Chelsea – were openly critical about the systems of medical care that meant he, as the first African American to receive a transplant, was effectively used as a form of data, but without any recognition of the costs involved. Everyone involved in the field of VCA was benefitting in some way, Robert remarked – surgeons developing their careers and their grants; institutions developing centres; the field supposedly becoming more advanced – but what of patients like him, whose bodies and consent were critical to that advancement, but without any similar financial or ethical recognition.

Robert’s remarks were not engaged with by the panel members, other than the statement that nobody present was being paid for their involvement, but they are critical in understanding the history of medical innovation and its need for consenting bodies – at least since the Nuremberg Code.

Following Robert, I stressed the importance developing evaluation measures and metrics based on the subjective experiences of patience. This includes not only the physical experience of having a hand or face transplant, or the ways in which adherence to an immunosuppressant regime brings its own medical challenges, but also the emotional and social aspects of facial transplantation that are less commonly considered. And this neglect isn’t surprising given both the history of medical experimentation and the continued difficulties in measuring emotions as easily as one might, say, blood pressure or cell count.

Moreover, the development of surgical specialisms needs to recognise the historical and ongoing subtexts at work in medical encounters, from the history of slavery and experimentation on black bodies to the gendering of appearance.

The history of medicine matters to the practice of medicine now in complex and entangled ways, as Interface shows. It is impossible to talk about innovation of any kind without reference to the lived experience of human subjects, and the ways surgery is conceived of, practiced, and evaluated. Too often those on the receiving end of medical innovation (and indeed many forms of technological change) are the last to be consulted. The NASEM committee workshop marks an important shift in the right direction. We need to build on that and create space for more voices and more perspectives.

With thanks to the NASEM committee for inviting me to speak, and to my fellow presenters: Martin Iglesias (Angeles del Pedregal Hospital, Mexico); Simon Kay, Leeds Teaching Hospital; Laurent Lantieri, Université de Paris, HEGP Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, France; Patrik Lassus, University of Helsinki, Finland; Mohit Sharma, Amrita Hospital, Faridabad