The Author

Fay Bound Alberti

This blog by Fay Bound Alberti was originally published on 17 February 2020 by Foundation for Science and Technology.

Facial recognition is increasingly commonplace, yet controversial. A technology capable of identifying or verifying an individual from a digital image or video frame it has an array of public and private uses – from smartphones to banks, airports, shopping centres and city streets. Live facial recognition will be used by the Metropolitan Police from 2020, having been trialled since 2016. And facial recognition is big business. One study published in June 2019 estimated that by 2024 the global market would generate $7 billion of revenue.

The proliferation and spread of facial recognition systems has its critics. In 2019, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee called for a moratorium on their use in the UK until a legislative framework is introduced. The concerns raised were ethical and philosophical as much as practical.

This is the context in which a ‘Facial Recognition and Biometrics – Technology and Ethics’ discussion was convened by the Foundation for Science and Technology at the Royal Society on 29 January 2020. Discussants included the Baroness Kidron, OBE, Carly Kind, Director of the Ada Lovelace Institute, James Dipple-Johnstone, Information Commissioner’s Office, Professor Carsten Maple, Professor of Cyber Systems Engineering at the University of Warwick, and Matthew Ryder QC, Matrix Chambers. Their presentations are referred to below, and available here.

Like any technology, facial recognition has advantages and disadvantages. Speedy and relatively easy to deploy, it has uses in law enforcement, health, marketing and retail. But each of these areas has distinct interests and motivations, and these are reflected in public attitudes. There is greater acceptance of facial recognition to reduce crime than when it is used to pursue profit, as discussed by Carly and Matthew.

This tension between private and public interest is but one aspect of a complex global landscape, in which the meanings and legitimacy of the state come into play. We can see this at work in China, one of the global regions with fastest growth in the sector. China deploys an extensive video surveillance network with 600 million+ cameras. This is apparently part of its drive towards a ‘social credit’ system that assesses the value of citizens, a plot twist reminiscent of the movie ‘Rated’ (2016), in which every adult has a visible ‘star’ rating.

This intersection between fact and fiction is relevant in other ways. Despite considerable economic and political investment in facial recognition systems, their results are variable. Compared to other biometric data – fingerprint, iris, palm vein and voice authentication – facial recognition has one of the highest false acceptance and rejection rates. It is also skewed by ethnicity and gender. A study by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology found that algorithms sold in the market misidentified members of some groups – especially women and people of colour –100 times more frequently than others.

It is unsurprising that technology betrays the same forms of bias that exist in society. As Carsten identified, we need to understand facial recognition, as other forms of biometrics, not in isolation but as part of complex systems influenced by other factors. The challenge for regulators is not only the reliability of facial recognition, but also the speed of change. It is a difficult task for those tasked with regulating, like James, who has urged greater collaboration between policy-makers, innovators, the public and the legislators.

From a historical perspective, these issues are not new. There is often a time lag between the speed of research innovation and the pace of ethical understandings or regulatory and policy frameworks. It is easy for perceived positive outcomes (e.g. public protection) to be framed emotively in the media while drowning out negative outcomes (e.g. the enforcement of social inequity). Ethical values also differ between people and countries, and the psychological and cultural perception of facial recognition matters.

We can learn much about the emergence, development and regulation of facial recognition systems by considering how innovative technologies have been received and implemented in the past, whether the printing press in the sixteenth century or the telephone in the nineteenth. Whatever legitimate or imagined challenges are brought by new technologies, it is impossible to uninvent them. So it is important to focus on their known and potential effects, including how they might alleviate or exacerbate systemic social problems. History shows that it is the sophistication of policy and regulatory response – that includes consulting with the public and innovators – that determines success.

Historical context is equally critical to understanding the cultural meanings of facial recognition. In the 18th century, the pseudoscience physiognomy suggested that character and emotional aptitude could be detected via facial characteristics, in ways that are discomfortingly similar to the ‘emotion detection’ claims of some facial recognition systems. In the 21st century it has similarly and erroneously been claimed that sexuality or intelligence could be read in the face. Faces, it is presumed, tell the world who we are.

But technology is never neutral. And not all people have publicly ‘acceptable’ faces, or the faces they had at birth. Facial discrimination is a core element of the #VisibleHate campaign.

By accident or illness, surgery or time, faces have the capacity to change and transform. Sometimes this is deliberate. Facial recognition technologies can be occluded and confused – by masks, by camouflage (like CV Dazzle), by cosmetic and plastic surgery.

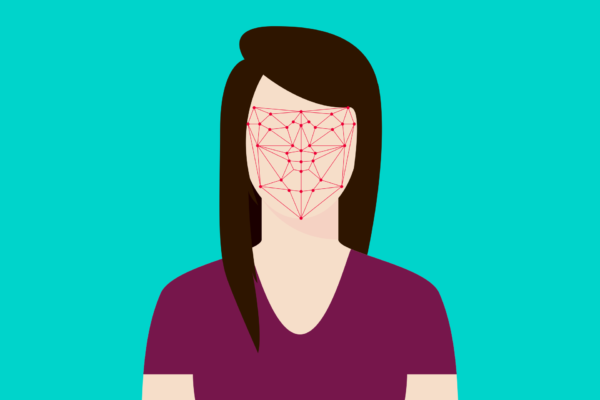

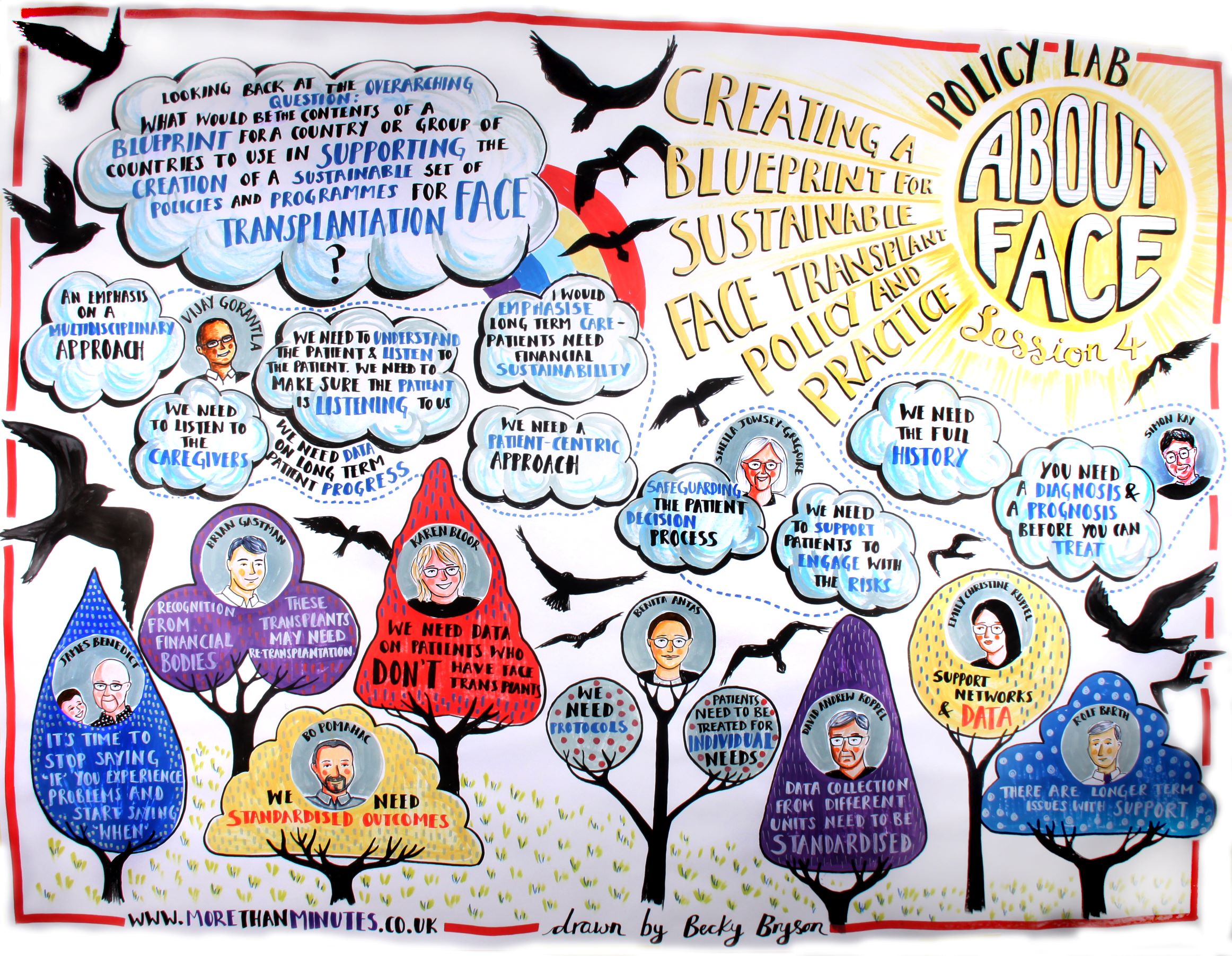

I work on the history of face transplants, an innovative and challenging form of surgical intervention reserved for the most severe forms of facial damage. Those undergoing face transplants do so for medical rather than social reasons, though that line can be blurred by contemporary concerns for appearance. Whether recipients’ sense of identity and self-hood is transformed by a new face is a subject of ongoing debate. Yet the capacity for radical transformation of the face exists.

Facial recognition technology not only raises questions about the ethical, legal, practical and emotional use of biometric evidence, but also presumes the face is a constant, individual unit of identity. What happens, on an individual and a social level, if that is not the case?

Author Bio

Prof Fay Bound Alberti, Professor of Modern History, UKRI Future Leaders Fellow and Director of Interface