The Author

Barry Gibb

A guest blog from Interface collaborator Barry Gibb, as part of our series of outputs for the Being Human Festival, November 2020.

Reflecting on Reflections

I’m not a fan of the mirror, avoiding them rather than seeking reflections. While my consciousness, how I see and perceive the world, is entirely unique to me, my face, it seems, can only be truly known by others.

The problem with this is that every time I see myself in a mirror, it’s a bit of a jolt, an ‘aha’ moment, as I scrutinise this body part so much of my identity is pinned to. Over time, it’s become an itinerary of failures. My cheekbones are not high enough. One eye is wider and possibly higher than the other. My lips are too thick, nose too wide. I live in constant dread of it getting fat. I do what I can to keep wrinkles at bay, even though, in my heart, I know that ageing is a privilege.

The mirror is a truth that shatters the belief I allow my mind to hold onto of how I appear to others. Like I said, I’m not a fan.

Society’s obsession

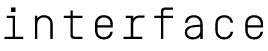

Which is why working on the AboutFace project is so utterly beguiling and uplifting – it affords the opportunity to explore society’s obsession with and attitudes towards the ‘boat race’, the mug. But the project delves far deeper than my/our own personal insecurities. We now live in a world in which face transplantation is possible. A world in which, whether through accident, illness or mishap, there are those whose face demands a level of reconstructive surgery that borders on the magical.

This is humbling. At one end of this magical spectrum are the surgical teams pioneering techniques at the forefront of reconstructive surgery. At the other are people whose lives have been dramatically impacted by the significant loss of, or damage to, their face.

But this is a bit like talking about the issues of poverty and limiting one’s understanding of the impact it has on a person to them simply ‘not having money’. For something each of us rarely sees, a face’s impact is largely a reflection of how others react to us – other people are our mirror. The face is such an integral part of human identity, communication and interaction, that the consequences of its ‘absence’ must be far reaching and hugely emotionally complex for those living with facial difference.

But while much of society seems content to accept the replacement of other, internal parts of the body, such as the heart, kidney or liver – when it comes to replacing faces, there is a far more complicated, visceral, often negative, reaction. Clearly then, the face is not just an organ. It is a body part that carries tremendous emotional and psychological weight.

Faical Meaning

Facial meaning and our reaction to ideas of transplantation is what I want to help the AboutFace team tease apart during the upcoming Being Human Festival. As a documentary filmmaker, the only thing that matters to me is what’s in front of the camera. And if there’s one thing that’s become powerfully evident during the many interviews I’ve conducted, a person’s face is just the beginning of the journey of who they are.

Working with the AboutFace team, the general public, invited guests and the wonderful artist, Clare Whistler, I’ll be turning my full attention to this emotionally tangled area where the limits of scientific and human endurance merge. We want to ignite imaginations, stimulate conversations and challenge perceptions – of transplants, faces, you!

Because, maybe it’s just me, but there seems to be a peculiarly British response to this subject matter. Despite half the western world intent on capturing a photo of their best self, in the best light and applying a beautifying filter to it, we also seem emotionally reluctant or unable to discuss issues surrounding a less than perfect face, whatever that is.

Author Bio

Patrick Adamson is an editor and independent film researcher who lectured at the University of St Andrews from 2021 until 2022, having received his PhD from there in 2020. Specialising in silent Westerns, early popular historical filmmaking, and universalist discourses in 1920s Hollywood, he has been published in journals including Film History and received awards for his research from BAFTSS (British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies) and SERCIA (Société pour l’Enseignement et la Recherche du Cinéma Anglophone).

He is a member of the Face Equality International Lived Experience Working Group.