The Author

Fay Bound-Alberti

Blog originally posted at the Net Gains site.

In our latest piece for Net Gains? Professor Fay Bound-Alberti discusses how the technological face race is one example of how an interdisciplinary approach is crucial to understanding the future of technological advancements in medicine.

The face race

In 2005, Amiens – France, the first face transplant in the world took place. The recipient was a 38-year woman, Isabelle Dinoire, whose face had been mauled by her pet Labrador while she was unconscious. There had been discussion since the 1980s of the potential of a face transplant one day, though France was a surprise forerunner. It was Peter Butler’s team at the Royal Free in London that was popularly, at least in the British media, expected to be first past the post; to win the face race. That very language – of medical firsts – is important, because all technological innovation involves the desire to improve, to enhance, to create, to push current practice in the presumed spirit of ‘progress’ forward in leaps and bounds, rather than inches. For the winners there is kudos and often riches – prestigious research grants, professional reputations. Along the way, however, there are failures, and risks.

In medical contexts, technological innovation is especially fraught, for the risks that are involved involve human subjects – especially those who are in a fragile emotional or physical state, sometimes on the brink of death. Each of us wants our medical professional, especially surgeons, to be enormously skilled and experienced in the procedure that we need – to have undertaken ‘more transplants than you’ve had hot dinners’ as one cardiac specialist said to me. But someone must be first to receive a new procedure, as well as the first to undertake it. The history of medicine is littered with so-called ‘guinea pigs’ on whom technological interventions have been tested, and not always successfully. The cardiac surgeon Christiaan Barnard made it to the cover of TIME magazine for his first successful heart transplant in 1967 but his patient – Louis Washkansky – lived only 18 days.

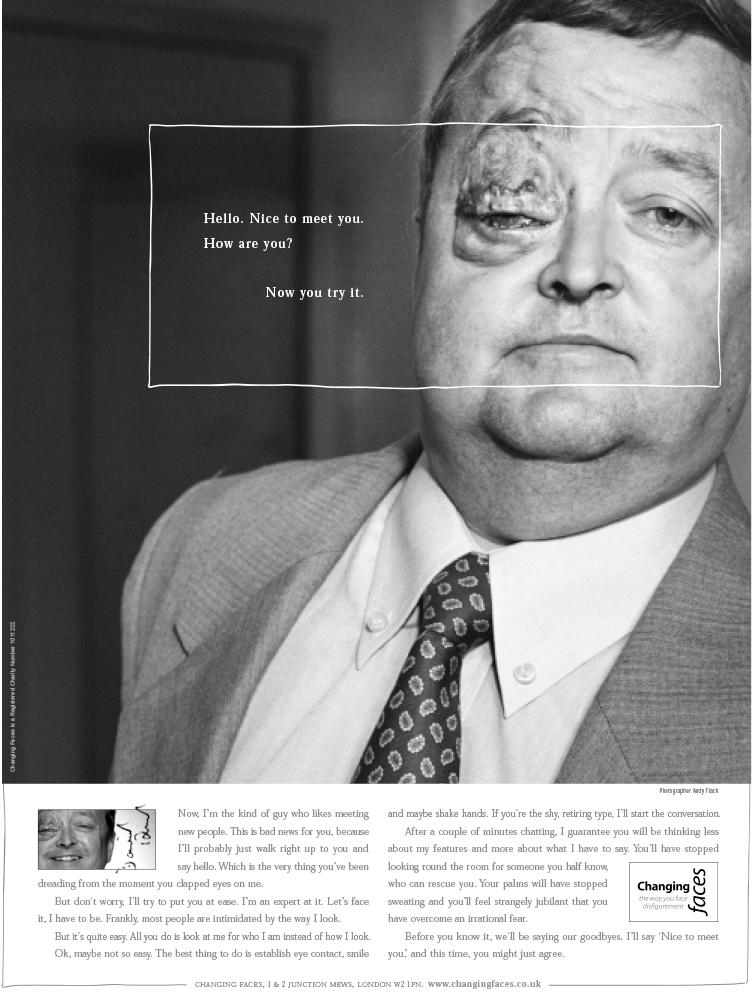

Face transplants, like hand transplants, are undertaken to enhance rather than save lives – though ‘Quality of Life’ is a much-debated concept. It is often possible to reconstruct faces using an individual’s own tissue, or to involve advanced prosthetics, just as technological innovation is increasingly able to emulate the touch and functions of a human hand. So why choose a face transplant?

Face transplants are a functional and aesthetic choice; reconstructed faces can have a taut and patchwork appearance, with burn patients needing multiple, ongoing operations. The complex skin and nerves around the mouth cannot be reconstructed by traditional means. In medical terms, face transplants are rare and risky procedures – even more than hand transplants; there have been fewer than 50 around the world since Isabelle Dinoire’s pathbreaking operation. There are many reasons for this: a lack of donors (few people want to give away the faces of their loved ones); a limited number of multidisciplinary teams with the skills to undertake the procedure; prohibitive costs – and in countries like the US no third-party insurance coverage – and the risks of taking immunosuppressants. Ten of those people who received face transplants have died of complications relating to the procedure, of cancer (like Isabelle Dinoire, who died at just 49), or by suicide. Two people have received re-transplants when their faces failed.

The future of face transplants is uncertain, especially as the large experimental grants given by the US Department of Defense are running out. New technologies are being adapted and developed to take their place, with tissue engineering being held up as the future promise for patients. Tissue engineering is a branch of Regenerative Medicine that combines stem cells and biomaterial scaffolds to restore organs after injury or disease. Emerging technologies relevant to face and hand transplants include 3D bioprinting, bio fabrication, pluripotent stem cells that are capable of self-renewing, and developing into the three kinds of cells that make up the human body. At present, tissue engineering plays a relatively small role in patient treatment and the procedures are still experimental and costly. These new technologies also come with their own controversies – around animal experimentation, human tissue use, informed consent, scientific integrity, and societal impact. The history of medicine informs us that ethics all too often fall by the wayside once a procedure moves from the bench to the bedside.

The Arts and Humanities play a critical role in helping navigate the complex questions of risk and ethics, of quality of life and the value of human experience. In the case of face transplants, qualitative research is critical to help surgeons evaluate patient outcomes. The experience of drinking through a straw might be a clinically measurable way of determining the success of a transplanted face. How it feels to kiss a loved one with the mouth of another, or to be kissed by that mouth, is not. But it isintegral to the human experience of facial transplantation, as explored by my Interface project, which is funded by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship and uses interdisciplinary methodologies to understand the emotional impacts and ethics of surgical experimentation. Interface explores themes relevant to a wide range of technological interventions: from facial recognition systems to deepfakes; from identity politics to cosmetic surgery, from 3D printing to transplanted faces. Such interventions tend to reflect rather than subvert traditional ideas about race, gender, ethnicity, and ability. How we live well with technologies of the face is a pressing ethical and social question.

The Interface project is housed in the Department of History at King’s within the Faculty of Arts and Humanities. The project is affiliated to the Centre for Technology and the Body, directed by Professor Fay Bound-Alberti ,as part of the Digital Futures Institute.

Further reading

[carousel_slide id=’329′]