The Author

Phyllida Swift

This blog on artificial intelligence and facial discrimination is the fourth and final installment of our series on facial recognition. Don’t miss our first blog by AboutFace PI Fay Bound Alberti, about what history can teach us about technological innovation, our second by guest author Dr Sharrona Pearl, on human facial recognition, face blindness and super-recognisers, or our third by George King at the Ada Lovelace Institute, on regulating facial recognition technologies.

Artificial Intelligence and Facial Discrimination

Over the past couple of years, here at Face Equality International we have experienced increasing numbers of requests from academics, policymakers, government bodies and businesses to input into commentary and research on artificial intelligence, and in particular ethical considerations around the effect of AI technologies on the facial difference community. The most obvious technology of concern is facial recognition and its potential for bias, exclusion and censorship. All of which are issues with a growing evidence base, but with little progress or acknowledgement of such evidence from technology companies, regulators, or businesses adopting AI into their practice.

At Face Equality International (FEI), we campaign as an Alliance of global organisations to end the discrimination and indignity experienced by people with facial disfigurements (FD) around the globe. We do this by positioning face equality as a social justice issue, rather than simply a health issue, which is all too often the case.

For any equality organisation, the public dialogue on how AI has been proven to replicate and reinforce human bias against marginalised groups is deeply concerning. Granted, it’s reassuring to see increased recognition in society, but this is not without great fear from social justice movements that generations of advancements could relapse at the hands of unregulated AI.

Because as it stands, AI is currently unregulated. A regulatory framework is in development for Europe, but ‘the second half of 2024 is the earliest time the regulation could become applicable to operators with the standards ready and the first conformity assessments carried out.’

Back in March, I was invited to share a statement at an event attached to the United Human Rights Council led by Gerard Quinn, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This came off the back of a thematic report into the impact of AI on the disabled community. The themes in this blog will follow similar lines as the statement, in less formal terms.

AI and the disabled community

It’s unsurprising that the most apparent AI-related threat that is relevant to us is facial recognition software. For an already marginalised and mistreated community, AI poses the threat of further degrading treatment. For instance, we already see constant abuse and hate speech on social media, where people with facial differences are referred to as ‘sub-human’, ‘monster’, or ‘that thing’. But algorithms often fail to pick up on such slurs as being derogatory to the facial difference (FD) community, which should fall into the protected group under disability policies.

Social media also poses the problem of censorship through AI, where on several occasions we have seen photos of people with disfigurements blurred out and marked as ‘sensitive’, ‘violent’, ‘graphic’ content. When reported, platforms and their human moderators are still failing to remove these warnings.

There is growing evidence to demonstrate the extent of harms caused by AI software in disadvantaging certain groups. Such as when Google Photos grouped a photo series of black people into a folder titled, ‘gorillas’. We know that several FD community members have reported having their photos blurred out and marked as sensitive, graphic or violent on social media, effectively censoring the facial difference community and inhibiting their freedom of expression to post photos of their faces online.

We know from research that many people make assumptions about someone’s character and ability based on the way they look. A study in America from Rankin and Borah found that photos of people with disfigurements were rated as significantly ‘less honest, less employable, less intelligent, less trustworthy’, the list goes on – when compared to photos where the disfigurement was removed.

AI, Dehumanisation, and Negative Bias

Sadly, we’re seeing these assumptions play out in AI led hiring practices too, where language choice, facial expression, even clothing have been shown to disadvantage candidates, whose scores are affected negatively. In a notorious Amazon example, a machine had taught itself to search for candidates using particular word choices to describe themselves and their activities, which ended up favouring male candidates who more commonly used those words. How can we expect someone with facial palsy, for example, to pass tests based on ‘positive’ facial expressions.

We have heard several cases of passport gates failing to work for people with facial disfigurements, and the same goes for applying for passports and ID online. Essentially, this is because the various software tests required to submit photos are not recognising people’s faces as human faces when they are put through. For an already all too often dehumanised community, this is simply not good enough.

Non-recognition of people with disfigurements was recorded by World Bank when it was found that someone with Down’s Syndrome was denied a photo ID card as the technology failed to recognise his non-standard face as a face. This was also apparent for people with Albinism.

There are often alternative routes to verify identity outside of facial recognition, for instance when problems arise with smartphone apps which rely on facial recognition to access bank accounts or similar services. Systems which ask the user to perform an action – such as blinking – can cause difficulties for people with some conditions, such as Moebius Syndrome or scarring. Some apps offer an alternative route for people unable to use the automatic system, but this goes against the principle of inclusive design and may be more cumbersome for people with facial differences. As is often talked about in disability spaces, the additional admin required of someone with a disability or disfigurement can take an emotional toll. Self-advocacy of this kind can be a life-long occupation.

Ethical AI?

So the problem for us is not necessarily in proving that there is a glitch in the system, it lies in making ourselves known to the technological gatekeepers. Those with the power to turn the tide on this ever-evolving issue. Whilst building coalitions with fellow organisations pushing for ethical AI, such as Disability Ethical? AI.

Princeton University Computer Science professor, Olga Russakovsky, said, “A.I. researchers are primarily people who are male, who come from certain racial demographics, who grew up in high socioeconomic areas, primarily people without disabilities.” “We’re a fairly homogeneous population, so it’s a challenge to think broadly about world issues.”

What’s interesting to note is that when we have asked our communities to relay to us their potential concerns about the growing use of AI, across every aspect of society, through polls and forms promoted across social media and via our membership, the response has been rather limited. There is often a consistent dialogue between us and our online communities when discussing issues that affect the FD community, but it appears that when it comes to AI, there has been far less of a response.

A ‘Transparency Void’

After further investigation, our team believes this could be for a number of reasons. Firstly, AI is too broad a technological term that conjures up distant, futuristic notions of robots driving our cars and taking over the planet. Which is very much what I thought of when this topic first landed on my own desk.

The second potential reason could be what we’ve started to refer to in our commentary on the issue as a ‘transparency void’. Meaning that it is far less obvious when a machine is creating barriers, bias or discriminating against an individual on the grounds that they are facially diverse, than it is if it were to be a human giving away cues in their language, their eye contact and their behaviours. In a recent Advisory Council meeting, a member spoke of the frustrations of trying to navigate automated phone lines with set questions, when your facial difference also affects speech. How does one get through to an actual human when there is no option to pass certain automated tests?

AI discrimination will continue to place the burden on the victim of the discrimination to challenge the decision, rather than on the (often well-resourced) entity using the technology. Existing research shows that the number of cases brought in relation to breaches of employment law legislation is just a tiny fraction of those which occur, so this is not an effective enforcement mechanism.

A Rapidly Escalating Issue

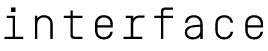

This is perhaps the most insidious threat regarding the negative impact of AI on furthering the face equality movement. Who do we hold accountable when AI discriminates based on facial appearance? Because we know for sure that it is already happening, as therein lies another fear for us at FEI, in that many members of the FD community will already be experiencing disadvantages at the hands of AI, without realising it, or without comprehension for how quickly this issue is escalating, with the use of AI in recruitment, security, identification, policing, assessing insurance, financial assessments and across our online spaces. These are not emerging technologies, AI is already here with us in force, and it’s growing exponentially.

It seems the crux of the issue lies in narrow data sets. In simple terms, the faces that AI is used to seeing are only certain types of faces. ‘Normative’, non-diverse, non-facially different faces that is.

We at FEI want to get to the source of the problem, and prevent further damage. It is our understanding, as a social justice organisation, as opposed to a tech company, that the best way to do this is to lend ourselves to the meaningful, robust and ethical consultation and involvement of our community. Whether it’s a question of us supporting companies to widen the pool of faces to diversify their date sets, or us continuing to feed into research and policy consultation, we are committed to making our cause, and the people we aim to serve known to the companies that so often ignore them.

Author Bio

Phyllida is CEO at Face Equality International. Phyllida was involved in a car accident in Ghana in 2015 and sustaining facial scarring. After which, she set out to reshape the narrative around scars and facial differences in the public eye, to champion positive, holistic representation that didn’t sensationalise, or other the facial difference community any further. She started out by sharing her story as a media volunteer for Changing Faces, before taking on a role as Campaigns Officer, and later Manager. During that time, she led the award winning, Home Office funded disfigurement hate crime campaign, along with working on multiple Face Equality Days, ‘Portrait Positive’ and ‘I Am Not Your Villain’. She shared her own experiences of how societal attitudes and poor media representation impacted upon being a young woman with facial scarring in her TEDX talk in 2018. Phyllida sits on the AboutFace Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP).

Further reading

[carousel_slide id=’329′]